2022.

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Screenings:

World Premiere FIDMarseille - July 2022

Compétition Premier

Compétition GNCR

Compétition PRIX RENAUD VICTOR

Filmfest Oldenburg - Sept. 2022

German Premiere

Actoral - Oct. 2022

Festival of Art and Comteporary Writing

UNDERDOX - Oct. 2022

Closing Night Film

New Hampshire Film Festival - Oct. 2022

Grand Jury Award - Narrative

U.S. Premiere

REDCAT - 2022

LA Premiere

46th Sáo Paulo IFF - Oct. 2022

New Directors Competition

South American Premiere

American Film Festival - Nov. 2022

Spectrum Competition

Polish Premiere

RIDM - Nov. 2022

International Features Competition

Canadian Premiere

Black Canvas 7 - Aug. 2023

State of the World

Mexican Premiere

Canal 180 - Nov. 2023

Portugese National Broadcast

ICA London - coming Spring 2024

Beyond Interpretation

Institute of Contemporary Art

Public series

Press:

Senses of Cinema

MovieMaker

POV

PERSONA

Cinema Aqui

FID interview

...

synopsis

A man keeps his terminal illness a secret from his daughter so he doesn’t spoil her plans to move to the city. The actor who plays the father has this illness in real life. He and his wife, who plays the mom, have been married for 25 years and have raised each other's kids from previous relationships together, but have never had a child of their own - so in the film we cast an actress to play the daughter they never had, but always dreamed of.

We intended for this horizontally produced, community project to contribute to the re-materialization of political aesthetics and to through its process forge a working-class cinematic vocabulary in common.

...

written and directed by rob rice

cinematography by alexey kurbatov

produced by matt porterfield

produced by rui xu

produced by rob rice

produced by mark staggs

starring tracy staggs

starring mark staggs

starring nikki deparis

...

Runtime: 87 minutes

Language: english

4k

5.1

IMDB

Letterboxd

Senses of Cinema

MovieMaker

POV

PERSONA

Cinema Aqui

FID interview

...

synopsis

A man keeps his terminal illness a secret from his daughter so he doesn’t spoil her plans to move to the city. The actor who plays the father has this illness in real life. He and his wife, who plays the mom, have been married for 25 years and have raised each other's kids from previous relationships together, but have never had a child of their own - so in the film we cast an actress to play the daughter they never had, but always dreamed of.

We intended for this horizontally produced, community project to contribute to the re-materialization of political aesthetics and to through its process forge a working-class cinematic vocabulary in common.

...

written and directed by rob rice

cinematography by alexey kurbatov

produced by matt porterfield

produced by rui xu

produced by rob rice

produced by mark staggs

starring tracy staggs

starring mark staggs

starring nikki deparis

...

Runtime: 87 minutes

Language: english

4k

5.1

IMDB

Letterboxd

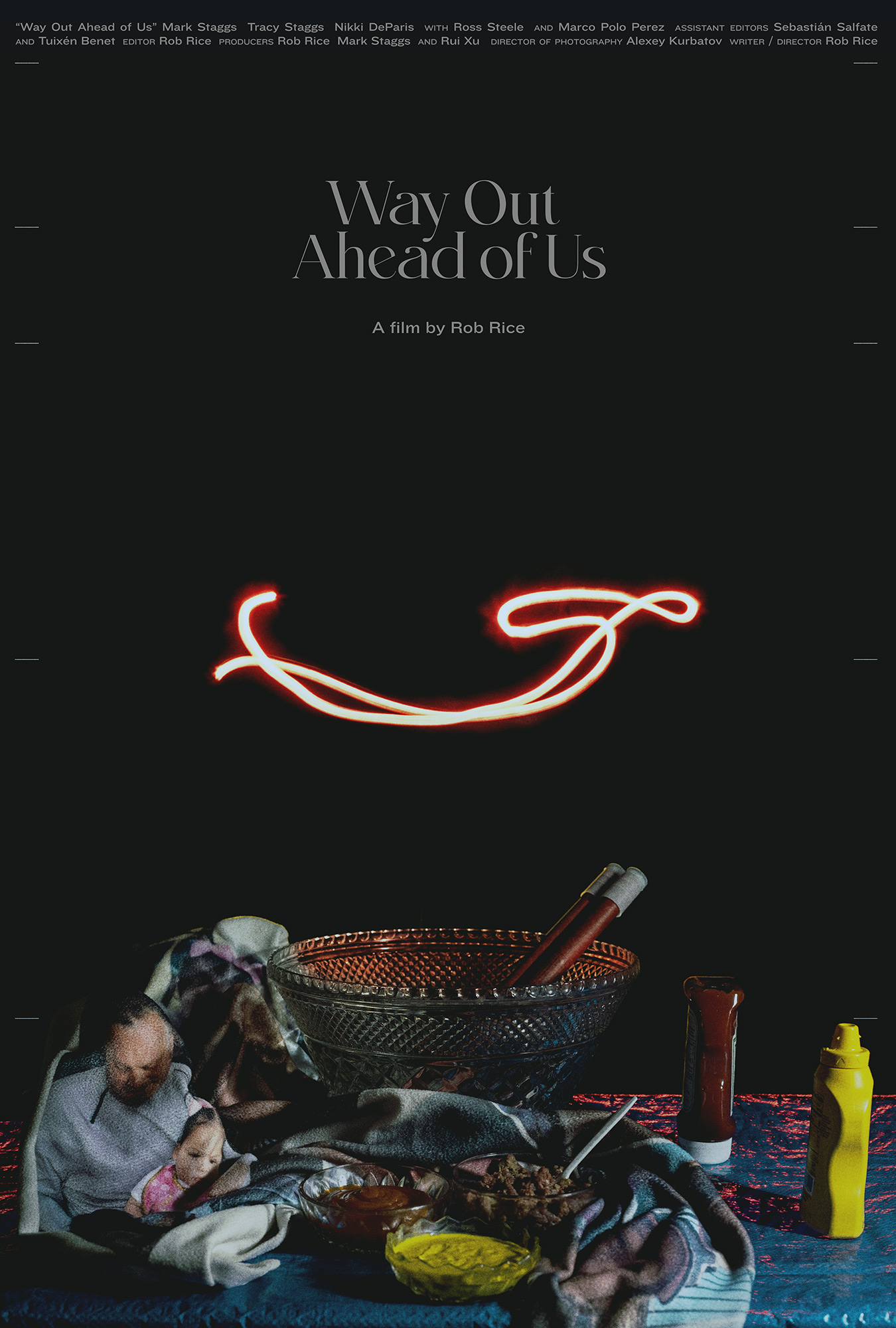

poster. by version industries.

director’s politics - Process

I chose a collaborative, participatory process, as opposed to pursuing some kind of observational documentary or fiction fully stylized as realism, to challenge the fraught contradictions of a film presented as faithfully portraying a community while couched in the POV of the outsider-filmmaker. By hybridizing our biographies, we embraced the change my presence made in the fabric of the place. The intention was that, once the explicitly surreal and acted sequences intervene, the fact of their participation, and the kind of relationship it means we have, would elevate the film from a portrait to a testament. I bet that, like with any artist, we would get the most insight into their condition through their creativity.

Conventionally, people are reduced to documentary objects at worst, subjects at best, but rarely are they agents. That agency is what our process sought to restore, through an explicit embrace of fiction and interest in the dynamics of performance. Sympathy ultimately naturalizes otherness, so we opted instead for solidarity. This horizontally produced, communal filmmaking process was an incubator for raising an aesthetic language in common. We believe that it’s possible to be intellectual without being academic, and that everyone is smart if you know how to listen to them, and as such, a real, re-materialized filmmaking politics is one that presents conversation between people, not about them, and leaves behind structures of mutuality that weren’t there before, and that live on long after the crew is gone.

director’s politics - Product

The US is the home of an obscene inequality in wealth, granting differential access to survival in a nation of surplus. In the shadow of this outrage, we need to make hidden, everyday, working-class American stories visible. I want the film to stand as a counter-narrative to the right-wing political currents that try to claim working-class white people as inherently symbolic of their cause, or the sanctimonious liberal idea that they’re all irredeemable vulgarians. In this cinematic landscape, so saturated by cliché, where are the leftwing titles? What does thier absence do to our political imagination? Where are the films that see this world as Debs and A. Phillip Randolph did; a site of deep fissures, but that hide profound potential solidarities, organizable around shared experiences of ruthlessness at the hands of creditors, employers and police? As neoliberalism has generalized immense precarity for everybody, maybe people are ready to finally trade in the wages of whiteness for class consciousness. I’m not naïve enough to think this will happen easily, but I’m sure it won’t if nobody offers an alternative story.

...

director’s statement

Obscure a place as it is, the time I’ve spent in Daggett has fundamentally changed who I am. It’s an unconventional, sometimes funny, always complex community where people have been forced to develop eccentric, autonomous and very beautiful ways to survive in the face of the world’s most perverse and indifferent political economy: America. I have to tell this story, of the town and of my experiences in it, to bring an audience to bear witness to something that would otherwise remain invisible.

This film is fiction. Much of the script is based on the lives of the (non)actors, but just as much is based on my own life. I not only depict what I saw there, but the eyes I was seeing it through, as a way to invoke a more complicated and yet more faithful image of the experience.

A note on the construction. The real Mark and Tracy have been married for more than twenty-five years and have helped to raise each other’s children from previous relationships. However, they have no children together. So, in order to open our process up to a dynamic and flexible imaginary space, I introduced a professional actor (Nikki DeParis) to play the daughter they never had. Mark’s illness however, though different from how I portrayed it, is very real.

I chose to set up the film this way, as opposed to pursuing some kind of observational documentary or fiction fully stylized as realism, to challenge the old contradictions of a film presented as faithfully portraying a community while situated in the POV of the outsider- filmmaker. By mixing our autobiographies, we embraced the change my presence made in the fabric of the place, instead of trying to deny it. The intention was that, once the explicitly surreal and acted fantasies intervene, the fact of their participation, and the kind of relationship it means we have, would elevate the film from a portrait to a testament to who they are. I knew that, like with any artist, we’d get the most insight into their condition through their creativity.

Nikki, whose own raw process is on display, unlocked and made visible so many details of the place, even before we began shooting. By giving me an outlet to really wield the story as a director, she helped me to channel my inspiration, the debts I owe to Apichatpong and Lucrecia Martel and Bi Gan and Pasolini, through the aesthetics of this process. Her presence enabled me to include my own story, to invoke my father’s mortality and my mother’s resilience and my own growing up, alongside theirs, so that by the end the everyday objects of their lives became almost ceremonially potent symbols of my own.

...

film politics statement

There’s a Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor quote that sums up a lot of what I believe about the real power of choosing who to spotlight on screen. Talking about American media culture, she writes:

We end up with a distorted view of American society – society looks richer, healthier, whiter than it actually is – life almost always looks easy – the effect is to convince ordinary people that their problems are their own. The American Dream mythology actually exists to justify its inverse – just as all success is attributable to personal responsibility, so are all failures. The more the lives of ordinary people are excluded, the more the American dream seems possible.

As is so succinctly said there, the exclusion of working-class American stories from the narrative landscape congeals in our cultural imagination to form a picture of the country that does not include how most people live. I cannot think of a more powerful mission for narrative practice; to burst the bubble that insulates wealth from its outght-to-be-obvious vulgarity.

However, unfortunately, so much of the (especially American) cinematic tradition that showcases the working-class is mired in either 1) an aesthetics of extraction that packages these lived experiences for an outside, upper-class gaze, or 2) right-wing ideology. In the second case, “working-class” is a rhetorical stand-in for white, and they’re conjured without complication and instrumentalized as a means to further racist ends. In the first case, we end up with supposedly sympathetic but ultimately distancing portrayals of class that cast it as inescapably alien. People are reduced to objects at worst, documentary subjects at best (subjects of a regime), but rarely are they agents.

This agency is precisely what our participatory process tries to restore, and with an explicit embrace of fiction and interest in the dynamics of performance, we hope to create a space where we center our subjectivities. It allows us – Mark, Tracy, Nikki and I – to reflect on our own stories, and to get to know each other well enough to borrow each others’. Instead of the distance that sympathy creates, or the false stylings of objectivity, we made something in solidarity and communion with each other.

...

crew bios

Rob Rice – Filmmaker – He/Him

Rob Rice is a filmmaker from western Massachusetts. Before changing careers, he completed an M.S. in Neuroscience at Tulane University and worked as an engineer in CRISPR genetics at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. He is currently living in Los Angeles, where he graduated from the MFA Film Directing program at CalArts, and where he was selected to attend the 2019 Flaherty Film Seminar as a Fellow. His work explores the personal and political economies of catastrophe and communion in America. His feature debut, Way Out Ahead of Us, premiered at FIDMarseille in the summer of 2022.

Matt Porterfield – Supervising Producer – He/Him

Matt has written and directed four feature films — Hamilton (2006), Putty Hill (2011), I Used to Be Darker (2013) and Sollers Point (2018) — all set in his native city of Baltimore. His work is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Harvard Film Archive and has screened at the Whitney Biennial, the Walker Arts Center, Centre Pompidou, Cinematheque Française, and film festivals such as Sundance, the Berlinale, San Sebastien, Rotterdam, BAFICI and SXSW. In summer 2014, he wrote and directed his first narrative short, Take What You Can Carry, with a grant from the Harvard Film Study Center. It premiered in the Shorts Competition at the Berlinale in 2015 and screened at Lincoln Center’s second annual Art of the Real series. The following year, he co-produced and co-wrote Gaston Solnicki’s first fiction feature, Kékszakállú, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. His most recent short, Cuatro paredes, was released by MUBI in 2021.

As a producer, Matt has participated in IFP’s No Borders, Cinemart, FIDLab, the Berlin Coproduction Market and the Venice Production Bridge. Matt is a Creative Capital grantee, the recipient of a Wexner Center Artists Residency, and a Guggenheim Fellow. He teaches screenwriting, critical theory and film production at Johns Hopkins University. Currently, he is based in Tijuana, Mexico.

Rui Xu – Post-Production Producer – She/Her

Rui Xu is an LA-based creative producer. She started her career, while pursuing her Producing MFA at CalArts, as a producer on Richard Van’s Hieu, which premiered at the 72nd Cannes International Film Festival. Rui’s first producing role on a feature project, Freddy Teng’s World of Tales, won the MPA Award at Beijing International Film Festival in 2019. The film, starring Lee Kang-sheng, recipient of the Golden Tiger Award from the Rotterdam Film Festival and lifelong collaborator of Tsai Ming-liang, is now in post-production.

Alexey Kurbatov– Director of Photography – He/Him

Alexey was born in Vologda, Russia, where he worked as a photographer before moving to Moscow to attend the School of New Cinema as a cinematographer. In addition to our film, he shot Detours, directed by his wife Ekaterina Selenkina, which was selected to premiere at the 2021 Venice Critic’s Week. He had just completed these projects when he passed away unexpectedly in January of 2020.

Colyn Cameron – Composer – He/Him

Colyn Cameron is a Canadian experimental musician who has released two albums on Vagrant Records as the acclaimed indie-pop outfit Wake Owl, and one solo album, Sad & Easy. He has done extensive touring and performing and has been nominated for a Canadian Juno award. He has done composing work for independent films and had songs licensed in TV shows and commercials. He’s currently working on another solo record and collaborating with musicians from a range of traditions on joint scoring projects.

...

cast bios

Nikki DeParis – She/Her

Nikki DeParis was born in New Jersey. She moved to Los Angeles in 2015, where she earned a BFA in Acting from the CalArts School of Theater. After graduating, she secured the starring role in the premiere presentation of Ashley Rose Wellman’s Hot Tragic Dead Thing at the Blank Theater. Recently she performed the English language dub for the character Amparo on HBOMax’s Veneno.

Mark Staggs (also contributed as a Producer) – He/Him

Mark was born and continues to reside in Daggett, CA, where he is the president of the board of the Community Service District and sitting member at the Silver Valley Unified School District. From age four to fourteen he and his family lived deep in the desert, three miles from the nearest road, without electricity or running water. Now a father and grandfather, he has worked in construction and towing throughout his adult life, and at one point owned and operated dozens of 25-cent candy vending machines around Barstow.

Tracy Staggs – She/Her

Tracy Staggs was born in Fontana, CA and moved to Daggett when she was 16. She takes pride in her work as a custodian at the Silver Valley High School. Privately, she is an avid fan of popular culture, with an encyclopedic knowledge of film, television and music. Because her grandmother is still alive, and her children from a previous marriage have recently had children of their own, she enjoys the rare honor of being both a grandmother and a granddaughter.

...

about the film

In 2017, I drove from Boston to Los Angeles over the course of a week, leaving my old and frustrating life in the labs of MIT behind, headed for film school. About a hundred miles from LA, I pulled off the highway to get gas and stretch my legs in Daggett. Though it appeared completely abandoned, something affected me about the little town.

After a few uneventful return trips where I encountered nobody (though one time, standing at an abandoned intersection, I heard a trumpet blurting out weird sounds that I was sure were some kind of taunt, but I could not for the life of me locate whoever was playing them), a waitress at trucker’s diner gave me Mark’s phone number. I’d lamely explained that I was interested in the history of the place, the mining. She shrugged and said, “I don’t really know what you’re talking about but here’s someone, if anyone will indulge you it’s him. His name is Mark Staggs.”

He pulled up fifteen minutes later and threw open the front passenger door. Because the power was out that day and the only available A/C was in the car, he drove me around with the whole family in tow, never asking what I was doing there, just excitedly pointing out various landmarks. Every once in a while, with no warning, we’d veer off the road onto some desert two-track, jostling along toward obscure hieroglyphics and abandoned mines. Hours later he dropped me off, saying, “next time you come out I gotta show you the Daggett Ditch!” And just like that there was a next time.

I went back, again and again until I was splitting my time between LA and Daggett, staying on their couch, meeting everyone in town, learning about all the intricate dramas and comedies in their orbit. A few months later, I was starting to organize ideas into a script. Eventually I presented them with this idea to make a film together and to bring an actress in.

We shot for four days at a time from October 2018 to May 2019 (with some additional shooting in early 2020 completed four days before Alex passed), for a total of 40 production days with a crew of 6-8, and then a dozen or so other trips with just Alex to shoot in a more stripped down, reactive style. Each time we would have a certain number of pages to do, scenes we had prepared and rehearsed and bought props for, but then we would also inevitably make something up in the moment. Many ultimately critical scenes came from this kind of spontaneity. Because we had this model where we’d come home for a week or two between shoots, I could watch the footage and react to it, devising new directions and fixes and storylines until ultimately the film became wildly different from the initial script.

My relationship there is very much ongoing. In the past few years, unrelated to the film, Mark and I have judged the community Christmas light competition, sold worms and carp on craigslist for his father, moved people in with their boyfriends and then out again, cleaned the dead owls out of a water tower, and flown my own parents out to finally close the loop. Ultimately, the project feels like just one of a million things we’ve done and, fingers crossed, will get to do together.

I chose a collaborative, participatory process, as opposed to pursuing some kind of observational documentary or fiction fully stylized as realism, to challenge the fraught contradictions of a film presented as faithfully portraying a community while couched in the POV of the outsider-filmmaker. By hybridizing our biographies, we embraced the change my presence made in the fabric of the place. The intention was that, once the explicitly surreal and acted sequences intervene, the fact of their participation, and the kind of relationship it means we have, would elevate the film from a portrait to a testament. I bet that, like with any artist, we would get the most insight into their condition through their creativity.

Conventionally, people are reduced to documentary objects at worst, subjects at best, but rarely are they agents. That agency is what our process sought to restore, through an explicit embrace of fiction and interest in the dynamics of performance. Sympathy ultimately naturalizes otherness, so we opted instead for solidarity. This horizontally produced, communal filmmaking process was an incubator for raising an aesthetic language in common. We believe that it’s possible to be intellectual without being academic, and that everyone is smart if you know how to listen to them, and as such, a real, re-materialized filmmaking politics is one that presents conversation between people, not about them, and leaves behind structures of mutuality that weren’t there before, and that live on long after the crew is gone.

director’s politics - Product

The US is the home of an obscene inequality in wealth, granting differential access to survival in a nation of surplus. In the shadow of this outrage, we need to make hidden, everyday, working-class American stories visible. I want the film to stand as a counter-narrative to the right-wing political currents that try to claim working-class white people as inherently symbolic of their cause, or the sanctimonious liberal idea that they’re all irredeemable vulgarians. In this cinematic landscape, so saturated by cliché, where are the leftwing titles? What does thier absence do to our political imagination? Where are the films that see this world as Debs and A. Phillip Randolph did; a site of deep fissures, but that hide profound potential solidarities, organizable around shared experiences of ruthlessness at the hands of creditors, employers and police? As neoliberalism has generalized immense precarity for everybody, maybe people are ready to finally trade in the wages of whiteness for class consciousness. I’m not naïve enough to think this will happen easily, but I’m sure it won’t if nobody offers an alternative story.

...

director’s statement

Obscure a place as it is, the time I’ve spent in Daggett has fundamentally changed who I am. It’s an unconventional, sometimes funny, always complex community where people have been forced to develop eccentric, autonomous and very beautiful ways to survive in the face of the world’s most perverse and indifferent political economy: America. I have to tell this story, of the town and of my experiences in it, to bring an audience to bear witness to something that would otherwise remain invisible.

This film is fiction. Much of the script is based on the lives of the (non)actors, but just as much is based on my own life. I not only depict what I saw there, but the eyes I was seeing it through, as a way to invoke a more complicated and yet more faithful image of the experience.

A note on the construction. The real Mark and Tracy have been married for more than twenty-five years and have helped to raise each other’s children from previous relationships. However, they have no children together. So, in order to open our process up to a dynamic and flexible imaginary space, I introduced a professional actor (Nikki DeParis) to play the daughter they never had. Mark’s illness however, though different from how I portrayed it, is very real.

I chose to set up the film this way, as opposed to pursuing some kind of observational documentary or fiction fully stylized as realism, to challenge the old contradictions of a film presented as faithfully portraying a community while situated in the POV of the outsider- filmmaker. By mixing our autobiographies, we embraced the change my presence made in the fabric of the place, instead of trying to deny it. The intention was that, once the explicitly surreal and acted fantasies intervene, the fact of their participation, and the kind of relationship it means we have, would elevate the film from a portrait to a testament to who they are. I knew that, like with any artist, we’d get the most insight into their condition through their creativity.

Nikki, whose own raw process is on display, unlocked and made visible so many details of the place, even before we began shooting. By giving me an outlet to really wield the story as a director, she helped me to channel my inspiration, the debts I owe to Apichatpong and Lucrecia Martel and Bi Gan and Pasolini, through the aesthetics of this process. Her presence enabled me to include my own story, to invoke my father’s mortality and my mother’s resilience and my own growing up, alongside theirs, so that by the end the everyday objects of their lives became almost ceremonially potent symbols of my own.

...

film politics statement

There’s a Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor quote that sums up a lot of what I believe about the real power of choosing who to spotlight on screen. Talking about American media culture, she writes:

We end up with a distorted view of American society – society looks richer, healthier, whiter than it actually is – life almost always looks easy – the effect is to convince ordinary people that their problems are their own. The American Dream mythology actually exists to justify its inverse – just as all success is attributable to personal responsibility, so are all failures. The more the lives of ordinary people are excluded, the more the American dream seems possible.

As is so succinctly said there, the exclusion of working-class American stories from the narrative landscape congeals in our cultural imagination to form a picture of the country that does not include how most people live. I cannot think of a more powerful mission for narrative practice; to burst the bubble that insulates wealth from its outght-to-be-obvious vulgarity.

However, unfortunately, so much of the (especially American) cinematic tradition that showcases the working-class is mired in either 1) an aesthetics of extraction that packages these lived experiences for an outside, upper-class gaze, or 2) right-wing ideology. In the second case, “working-class” is a rhetorical stand-in for white, and they’re conjured without complication and instrumentalized as a means to further racist ends. In the first case, we end up with supposedly sympathetic but ultimately distancing portrayals of class that cast it as inescapably alien. People are reduced to objects at worst, documentary subjects at best (subjects of a regime), but rarely are they agents.

This agency is precisely what our participatory process tries to restore, and with an explicit embrace of fiction and interest in the dynamics of performance, we hope to create a space where we center our subjectivities. It allows us – Mark, Tracy, Nikki and I – to reflect on our own stories, and to get to know each other well enough to borrow each others’. Instead of the distance that sympathy creates, or the false stylings of objectivity, we made something in solidarity and communion with each other.

...

crew bios

Rob Rice – Filmmaker – He/Him

Rob Rice is a filmmaker from western Massachusetts. Before changing careers, he completed an M.S. in Neuroscience at Tulane University and worked as an engineer in CRISPR genetics at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard. He is currently living in Los Angeles, where he graduated from the MFA Film Directing program at CalArts, and where he was selected to attend the 2019 Flaherty Film Seminar as a Fellow. His work explores the personal and political economies of catastrophe and communion in America. His feature debut, Way Out Ahead of Us, premiered at FIDMarseille in the summer of 2022.

Matt Porterfield – Supervising Producer – He/Him

Matt has written and directed four feature films — Hamilton (2006), Putty Hill (2011), I Used to Be Darker (2013) and Sollers Point (2018) — all set in his native city of Baltimore. His work is in the permanent collections of the Museum of Modern Art and the Harvard Film Archive and has screened at the Whitney Biennial, the Walker Arts Center, Centre Pompidou, Cinematheque Française, and film festivals such as Sundance, the Berlinale, San Sebastien, Rotterdam, BAFICI and SXSW. In summer 2014, he wrote and directed his first narrative short, Take What You Can Carry, with a grant from the Harvard Film Study Center. It premiered in the Shorts Competition at the Berlinale in 2015 and screened at Lincoln Center’s second annual Art of the Real series. The following year, he co-produced and co-wrote Gaston Solnicki’s first fiction feature, Kékszakállú, in Buenos Aires, Argentina. His most recent short, Cuatro paredes, was released by MUBI in 2021.

As a producer, Matt has participated in IFP’s No Borders, Cinemart, FIDLab, the Berlin Coproduction Market and the Venice Production Bridge. Matt is a Creative Capital grantee, the recipient of a Wexner Center Artists Residency, and a Guggenheim Fellow. He teaches screenwriting, critical theory and film production at Johns Hopkins University. Currently, he is based in Tijuana, Mexico.

Rui Xu – Post-Production Producer – She/Her

Rui Xu is an LA-based creative producer. She started her career, while pursuing her Producing MFA at CalArts, as a producer on Richard Van’s Hieu, which premiered at the 72nd Cannes International Film Festival. Rui’s first producing role on a feature project, Freddy Teng’s World of Tales, won the MPA Award at Beijing International Film Festival in 2019. The film, starring Lee Kang-sheng, recipient of the Golden Tiger Award from the Rotterdam Film Festival and lifelong collaborator of Tsai Ming-liang, is now in post-production.

Alexey Kurbatov– Director of Photography – He/Him

Alexey was born in Vologda, Russia, where he worked as a photographer before moving to Moscow to attend the School of New Cinema as a cinematographer. In addition to our film, he shot Detours, directed by his wife Ekaterina Selenkina, which was selected to premiere at the 2021 Venice Critic’s Week. He had just completed these projects when he passed away unexpectedly in January of 2020.

Colyn Cameron – Composer – He/Him

Colyn Cameron is a Canadian experimental musician who has released two albums on Vagrant Records as the acclaimed indie-pop outfit Wake Owl, and one solo album, Sad & Easy. He has done extensive touring and performing and has been nominated for a Canadian Juno award. He has done composing work for independent films and had songs licensed in TV shows and commercials. He’s currently working on another solo record and collaborating with musicians from a range of traditions on joint scoring projects.

...

cast bios

Nikki DeParis – She/Her

Nikki DeParis was born in New Jersey. She moved to Los Angeles in 2015, where she earned a BFA in Acting from the CalArts School of Theater. After graduating, she secured the starring role in the premiere presentation of Ashley Rose Wellman’s Hot Tragic Dead Thing at the Blank Theater. Recently she performed the English language dub for the character Amparo on HBOMax’s Veneno.

Mark Staggs (also contributed as a Producer) – He/Him

Mark was born and continues to reside in Daggett, CA, where he is the president of the board of the Community Service District and sitting member at the Silver Valley Unified School District. From age four to fourteen he and his family lived deep in the desert, three miles from the nearest road, without electricity or running water. Now a father and grandfather, he has worked in construction and towing throughout his adult life, and at one point owned and operated dozens of 25-cent candy vending machines around Barstow.

Tracy Staggs – She/Her

Tracy Staggs was born in Fontana, CA and moved to Daggett when she was 16. She takes pride in her work as a custodian at the Silver Valley High School. Privately, she is an avid fan of popular culture, with an encyclopedic knowledge of film, television and music. Because her grandmother is still alive, and her children from a previous marriage have recently had children of their own, she enjoys the rare honor of being both a grandmother and a granddaughter.

...

about the film

In 2017, I drove from Boston to Los Angeles over the course of a week, leaving my old and frustrating life in the labs of MIT behind, headed for film school. About a hundred miles from LA, I pulled off the highway to get gas and stretch my legs in Daggett. Though it appeared completely abandoned, something affected me about the little town.

After a few uneventful return trips where I encountered nobody (though one time, standing at an abandoned intersection, I heard a trumpet blurting out weird sounds that I was sure were some kind of taunt, but I could not for the life of me locate whoever was playing them), a waitress at trucker’s diner gave me Mark’s phone number. I’d lamely explained that I was interested in the history of the place, the mining. She shrugged and said, “I don’t really know what you’re talking about but here’s someone, if anyone will indulge you it’s him. His name is Mark Staggs.”

He pulled up fifteen minutes later and threw open the front passenger door. Because the power was out that day and the only available A/C was in the car, he drove me around with the whole family in tow, never asking what I was doing there, just excitedly pointing out various landmarks. Every once in a while, with no warning, we’d veer off the road onto some desert two-track, jostling along toward obscure hieroglyphics and abandoned mines. Hours later he dropped me off, saying, “next time you come out I gotta show you the Daggett Ditch!” And just like that there was a next time.

I went back, again and again until I was splitting my time between LA and Daggett, staying on their couch, meeting everyone in town, learning about all the intricate dramas and comedies in their orbit. A few months later, I was starting to organize ideas into a script. Eventually I presented them with this idea to make a film together and to bring an actress in.

We shot for four days at a time from October 2018 to May 2019 (with some additional shooting in early 2020 completed four days before Alex passed), for a total of 40 production days with a crew of 6-8, and then a dozen or so other trips with just Alex to shoot in a more stripped down, reactive style. Each time we would have a certain number of pages to do, scenes we had prepared and rehearsed and bought props for, but then we would also inevitably make something up in the moment. Many ultimately critical scenes came from this kind of spontaneity. Because we had this model where we’d come home for a week or two between shoots, I could watch the footage and react to it, devising new directions and fixes and storylines until ultimately the film became wildly different from the initial script.

My relationship there is very much ongoing. In the past few years, unrelated to the film, Mark and I have judged the community Christmas light competition, sold worms and carp on craigslist for his father, moved people in with their boyfriends and then out again, cleaned the dead owls out of a water tower, and flown my own parents out to finally close the loop. Ultimately, the project feels like just one of a million things we’ve done and, fingers crossed, will get to do together.